Coffee & Tea, Custom Pouches, Packaging Academy

Coffee Valve vs No Valve: When Does a Degassing Valve Reduce Risk—and When Does It Create New Failures?

If your coffee tastes great at launch but “dies” after shipping, the problem is rarely the roast. It is usually pressure, oxygen, and a packaging choice that was not validated for the route.

A degassing valve reduces risk only when CO₂ pressure is the dominant threat. If pressure is low, the valve often adds a new bond zone that can leak or become an oxygen shortcut. I prove seal integrity and valve-bond stability under stress before I choose “valve” or “no valve.”

When I troubleshoot coffee freshness or “puffy bags,” I do not debate features first. I map the failure pattern, identify the dominant risk (pressure vs oxygen), and then validate the full system: pouch + coffee + case + route stress.

What does “valve success” and “valve failure” look like in real coffee orders?

A valve is not “premium” if it creates returns. If customers smell less aroma, see oil stains, or receive swollen packs, they will blame the coffee—then they stop buying.

I define valve success as stable pack shape, stable aroma, and no leak trends after shipping. Valve failure is any slow drift: odor loss, micro-weeping, or a bag that feels sealed but leaks later.

How I translate complaints into failure modes

| Complaint | Likely dominant risk | Where I look first |

|---|---|---|

| “Puffy bag” | CO₂ pressure | Headspace, seal margin, valve flow/bond |

| “Flat aroma” | Oxygen ingress | Micro-leaks at seals or valve bond edge |

| “Oily/wet box” | Leak + route stress | Corners, top zone, valve bond drift |

From a production standpoint, this matters because two bags can look identical on day one, but one will drift under compression and vibration. I separate pressure symptoms from oxygen symptoms so I do not “fix” the wrong thing.

How does CO₂ timeline make “puffy bags” predictable, not random?

If a brand fills too soon after roasting, CO₂ will do what CO₂ does. The bag swells, and the weakest interface gets loaded first.

I treat degassing as a timeline problem: roast level, grind size, and pack timing decide how fast pressure builds. When the timeline is wrong, “puffy bags” are a measurement outcome, not a surprise.

What I check before I even talk about valves

| Variable | What it changes | What I do |

|---|---|---|

| Pack timing after roast | Peak pressure window | I align packaging choice to real fill day |

| Grind vs whole bean | Gas release rate | I raise valve priority for fast degassing formats |

| Headspace | Pressure buffering | I set a target range, not “as full as possible” |

In real manufacturing, this detail often determines whether a valve helps or just masks a weak seal. If pressure is not dominant, a valve may add complexity with no benefit.

When does internal pressure become the real risk driver for valve vs no valve?

A valve is useful when pressure is actively loading seals, corners, and top features. If pressure is low, the valve can be an unnecessary failure path.

I choose a valve only when the CO₂ timeline plus pack geometry makes pressure the dominant threat. If the risk is oxygen ingress, I prioritize seal integrity and barrier stability first.

My decision logic for “valve” vs “no valve”

| Scenario | Risk driver | My default |

|---|---|---|

| Early fill, active degassing | Pressure loading | Valve + stronger top-zone control |

| Late fill, low pressure | Oxygen ingress | No valve + higher seal margin/QC |

| Rough parcel route | Stress training | Validate both under compression/vibration |

From our daily packaging work, we see brands overpay for a valve when the real issue is a marginal seal window. I do not let “features” replace validation.

How do I protect seal window and hot tack when pressure loads the top zone?

If pressure is present, it does not “test” the valve first. It tests the weakest interface first, and that is often the seal system.

I lock the seal system before I trust the valve: seal window, hot tack margin, seal land width, and cooling. Pressure plus handling will find weak hot tack and turn it into micro-channels.

What I control so the seal survives pressure + handling

| Control point | Failure it prevents | How I verify |

|---|---|---|

| Seal land width consistency | Micro-channels | Measure by shift/time, not one sample |

| Hot tack margin | Early-stack leak paths | Hot-state handling simulation |

| Cooling/press time | Weak edges | Stress-first then leak trend checks |

From a production standpoint, this matters because small drift stacks up. A valve cannot save a seal that is already living at the edge of its process window.

Where do valve leaks actually start in the bonding zone?

Most “valve failures” are not valve defects. They are bonding failures that drift with adhesive, cure, contamination, and curl.

The valve creates a hole and a bond zone. If the bond edge forms a micro-channel, oxygen and aroma loss become predictable. I inspect bond-edge integrity, not just “it is stuck on.”

Valve bonding drift patterns I watch for

| Drift | What it causes | My response |

|---|---|---|

| Adhesive coat variance | Edge channels | Tighten coat targets + cure window |

| Film curl/top-zone warp | Uneven contact | Flatten top zone + control heat history |

| Dust/oil contamination | Weak bond spots | Clean handling + inspection gates |

In real manufacturing, this detail often determines whether the valve becomes an oxygen shortcut. I treat the bond edge like a seal, because functionally it is one.

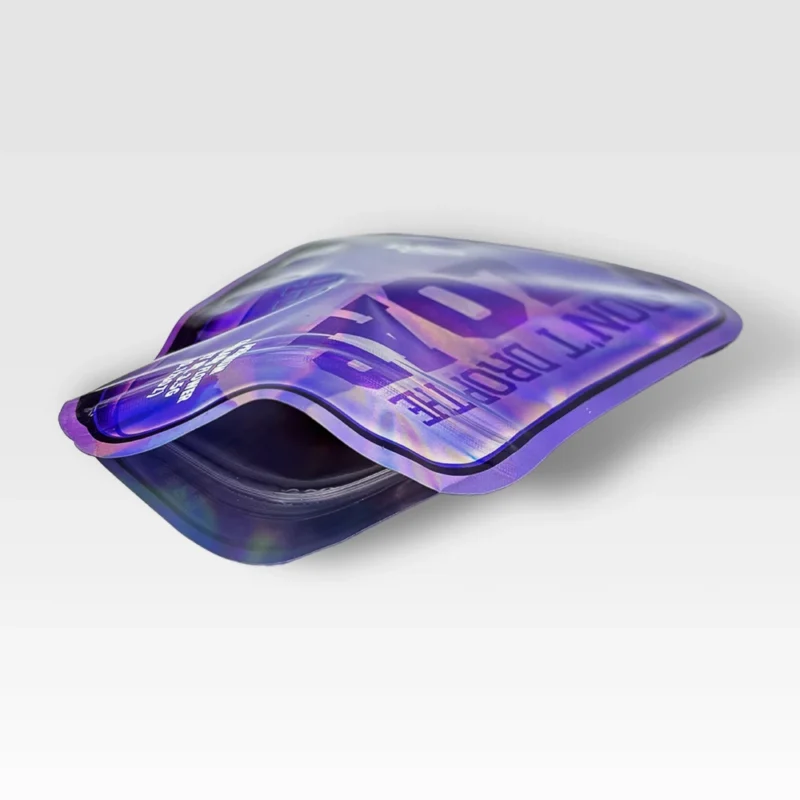

Why can a valve help aroma—or become an oxygen shortcut if misbuilt?

Barrier numbers only matter when the package is truly sealed. A micro-channel defeats great OTR the same way a cracked door defeats a strong wall.

A correct valve system can reduce pressure stress and protect seals. A misbuilt valve system can introduce oxygen ingress and flatten aroma faster than a no-valve pack.

Barrier vs leakage: what wins in real life

| What’s “good” on paper | What fails in reality | What I prioritize |

|---|---|---|

| Low OTR film | Micro-channel leak | Seal + valve bond integrity under stress |

| Strong seal strength | Hidden edge channels | Leak trend checks, not one pull test |

| Valve present | Bond drift after shipping | Compression/vibration first, then inspect |

From our daily packaging work, we see aroma complaints that look like “bad coffee” but trace back to oxygen shortcuts. I prove the package is sealed under stress before I chase higher barrier numbers.

Every premium feature is a tolerance stack. If the base system is marginal, features do not add value. They add failure paths.

Zippers can narrow seal margin, tear notches can start cracks, and windows can change stiffness and scuff behavior. If a pouch has a valve plus multiple features, I assume the interface zones will fail first.

Feature interactions I treat as “high-risk zones”

| Feature | New risk | What I do first |

|---|---|---|

| Zipper | Top-zone distortion | Lock seal land + top flatness |

| Tear notch | Crack initiation | Radius control + stress cycling checks |

| Window | Stiffness mismatch | Rub/scuff validation + corner checks |

From a production standpoint, this matters because feature zones often see higher local stress. I only add features after the valve/no-valve base choice is proven under route stress.

How do compression and vibration make valve problems show up after shipping?

If a pouch passes in the factory but fails after shipping, the route is teaching it to fail slowly. That is not bad luck. That is missing validation.

Compression can warp the top zone and distort the valve area. Vibration creates micro-slip that grows bond-edge channels. Thermal swings change stiffness and adhesion. That is why “day-one OK” can become “week-two weird.”

Route stress moments I design tests around

| Route moment | What it does | What it exposes |

|---|---|---|

| Stacking compression | Loads top zone | Seal/valve bond drift |

| Line-haul vibration | Creates micro-slip | Edge channels, abrasion growth |

| Temperature swings | Changes stiffness | Curl, bond fatigue, crack starts |

In real manufacturing, this detail often determines whether “valve vs no valve” even matters. If the case fit and route stress are ignored, both options can fail for preventable reasons.

What is my stress-first protocol to prove valve vs no valve?

I do not run a “pretty sample” test. I run a stress-first test, because slow failures only show up after abuse.

My validation unit is a system: bag + coffee + valve + case. I apply compression/vibration/thermal exposure first, then I track leak trends and aroma indicators. I want failures to appear early and repeatably.

My sequence that separates leak vs barrier problems

| Step | Why it is first | What I record |

|---|---|---|

| Compression + vibration | Creates drift | Leak trend, bond edge changes, curl |

| Thermal exposure | Changes stiffness/adhesion | Seal and valve bond stability |

| Integrity checks | Confirms oxygen shortcut | Micro-leak rate, not just pass/fail |

From a production standpoint, this matters because a one-time “passed” result can hide drift. I look for trends across time, rolls, and handling conditions so launch performance does not depend on luck.

Which Baseline / Upgrade / Premium spec paths do I shortlist—and what can still fail?

There is no “always valve” rule that survives the real world. There is only a validated system that matches your CO₂ timeline and route stress.

I deliver 2–3 spec paths with clear risk statements. Baseline is often no valve when pressure is not dominant. Upgrade uses a valve with tighter bonding control. Premium locks validation, QC gates, and change-control so performance holds at scale.

My shortlists (and the failure I still watch)

| Path | Best when | Still can fail if |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (No valve) | Low pressure, oxygen risk | Seal margin/QC is weak or pack-out rubs corners |

| Upgrade (Valve) | Active degassing, pressure risk | Bond edge drifts or top zone curls under compression |

| Premium (Valve + locked QC) | E-comm + harsh routes | Change-control is ignored (film/adhesive/valve swap) |

From our daily packaging work, we see most failures come from “small changes” after approval. I treat valve performance as a controlled system, not a one-time certification.

Conclusion

A coffee valve reduces risk when pressure is the dominant threat. If pressure is low, a valve can add a new oxygen shortcut. If you want a pouch that survives shipping, I can help you validate the full system.

FAQ

- Do all coffee bags need a degassing valve? No. I add a valve only when CO₂ pressure is a real risk driver for the pack and route.

- Why do valve bags still lose aroma? Most often because oxygen enters through micro-channels at seals or the valve bond edge, not because the film OTR is “too high.”

- What causes “puffy bags” the most? Early pack timing after roast, limited headspace, and a seal system without enough margin under pressure and handling.

- How do I test valve vs no valve the right way? Use a stress-first sequence: compression + vibration + thermal exposure first, then measure leak trends and bond drift.

- What changes can silently break valve performance? Adhesive changes, cure window drift, valve supplier swaps, and top-zone heat history changes during production.

This content is for packaging education. We do not sell any regulated products.

About Me

Brand: Jinyi

Slogan: From Film to Finished—Done Right.

Website: https://jinyipackage.com/

Our Mission

JINYI is a source manufacturer specializing in custom flexible packaging solutions. I want to deliver packaging that is reliable, usable, and repeatable, so brands spend less time on back-and-forth and get more predictable quality, lead time, structure, and printing outcomes.

Who I Am

JINYI is a source manufacturer specializing in custom flexible packaging solutions, with over 15 years of production experience serving food, snack, pet food, and daily consumer brands. We operate a standardized facility with multiple gravure printing lines and advanced HP digital printing systems, supporting both stable large-volume orders and flexible short runs. From material selection to finished pouches, we focus on process control and real-world performance on shelf, in transit, and at end use.