Custom Pouches, Food & Snacks, Packaging Academy

Foil, Flow Wrap, or Resealable Pouches for Chocolate: Which Barrier + Seal System Best Prevents Stale Aroma and Texture Drift?

Customers call it “stale,” “chalky,” or “weird texture.” Brands call it returns, shrink, and trust loss—often caused by a package-format mismatch, not “bad chocolate.”

The best format is the one that keeps oxygen and moisture exchange within your shelf-life budget and stays reliably sealed across real handling. Foil, flow wrap, and resealable pouches can all work, but each fails in a different place—usually at the seal.

Chocolate drift is rarely one mechanism. It is a combined outcome of oxygen exposure (aroma loss/rancidity), moisture gain or loss (texture drift and sugar-bloom risk), temperature cycling (fat-bloom acceleration), and seal integrity variance. Explore food packaging solutions that focus on barrier + seal repeatability.

What is each format actually built to do—and where does it usually fail?

High barrier does not matter if the package leaks. The format decides where leakage and drift are most likely to start.

The short answer is simple: foil wrap can block light and aroma well, flow wrap can seal fast at scale, and resealable pouches support multi-serve use—but each format has a predictable weak point that buyers should plan and test for.

Format strengths are real, but the leak path changes

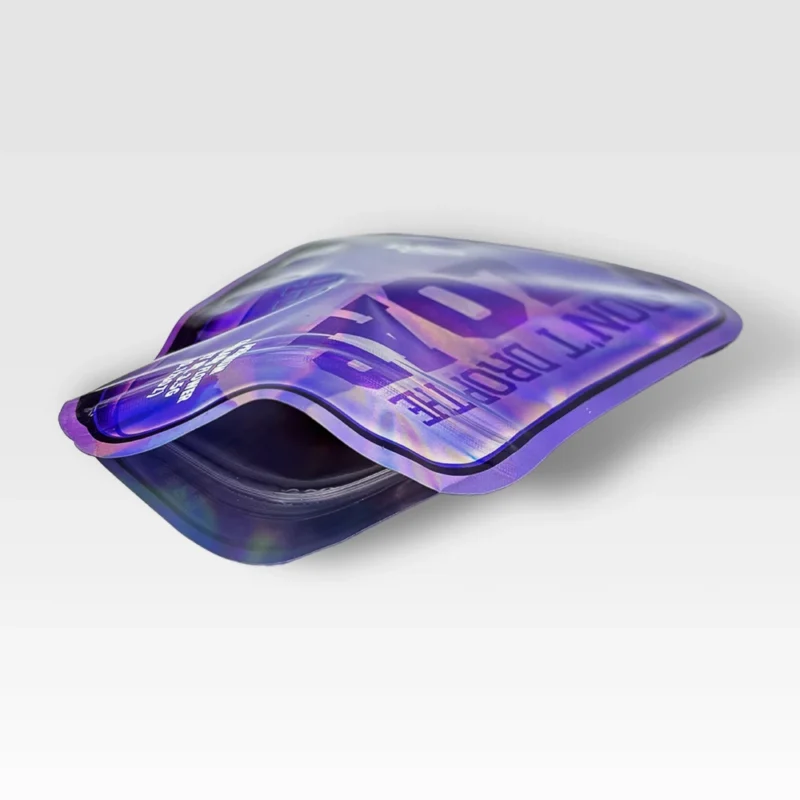

Foil wrap (foil/paper/foil laminates) can deliver strong barrier and light blocking, but folds and overlaps are not “true seals.” Performance depends on wrap overlap, fold tightness, and whether a secondary overwrap is used. Flow wrap (HFFS) is built for high-speed packing and consistent end seals. It can use cold seal to protect heat-sensitive chocolate, but it adds multiple seal lines and geometry risk (fin/back seal plus end seals). Resealable pouches are built for merchandising and multi-serve convenience, but post-opening drift is dominated by reseal reality. Zippers can trap crumbs, misalign, or partially close, creating micro-gaps that are invisible but meaningful over time.

| Format | Dominant strength | Dominant weak point | Best-fit scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foil wrap | Light + aroma barrier potential | Fold/overlap leakage variance | Bars with secondary protection |

| Flow wrap | High-speed sealing, repeatable lines | Multi-seal geometry + seal contamination | High-volume singles, retail units |

| Resealable pouch | Multi-serve convenience, display | After-opening zipper leakage variance | Sharing packs, assortments |

Evidence (Source + Year): Afoakwa (2009) describes how chocolate quality defects relate to structure and storage conditions, and why packaging must be paired with the product’s failure modes.

Which “stale” problem are you paying for: oxygen, moisture, light, or odor transfer?

“Stale aroma” and “texture drift” come from different exposures. If buyers do not separate them, they overpay for the wrong barrier and still get complaints.

Oxygen and aroma loss drive flavor drift, while water vapor exchange drives softness, stickiness, and sugar-bloom conditions. The winning structure is the one that hits OTR/WVTR targets for your shelf days and climate, while still sealing reliably.

Barrier targets should be written as shelf-life budgets

Oxygen ingress is a time problem. A little oxygen over many weeks can equal a lot of aroma loss. Moisture is also a time problem, but it is more sensitive to humidity swings and display conditions. Light and odor transfer add risk in open retail environments, especially when chocolate is stored near scented products. Foil-based structures often win on aroma and light blocking, but they are not automatically “best” if the wrap system is loose or if secondary packaging is missing. Flow wrap can deliver strong barrier depending on film choice, but only if seal lines remain clean and consistent. Resealable pouches can be excellent for barrier before opening, but after opening, drift often becomes a reseal control problem rather than a film problem.

| Complaint language | Likely exposure driver | What packaging can control | What to validate |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Smells flat / weak” | Oxygen + aroma loss | OTR + seal integrity | Headspace trend (if available) + leak screen |

| “Soft / sticky” | Moisture gain | WVTR + seal integrity | Humidity storage + texture checks |

| “Looks dusty / bloom” | Temperature cycling | Reduce external swings + light block | Thermal cycling + whiteness scoring |

Evidence (Source + Year): Afoakwa (2009) connects storage and structure to bloom and sensory changes, supporting the need to treat “stale” as multiple exposures, not one.

Why does temperature cycling accelerate bloom—and what can packaging realistically change?

Many bloom problems are not caused by “low barrier.” They are caused by temperature swings that accelerate fat mobility and recrystallization.

Packaging cannot rewrite internal fat migration physics, but it can reduce the external triggers that make bloom faster and less predictable: temperature shock, light exposure, and moisture/oxygen entry through weak seals.

Temperature exposure is a channel map, not a storage label

Retail drift often starts outside the factory: warm trucks, sunlit displays, and backroom temperature swings create repeated “heat-cool” cycles. Those cycles can accelerate bloom risk and surface changes. Packaging can help by reducing how much external variability reaches the product. Secondary packaging, shipper choices, and light-blocking layers can reduce exposure. Still, the most important practical rule is to treat bloom risk as a channel timeline: factory → warehouse → transport → retail shelf → consumer home. If the hottest points are late in the chain, “it looked fine at packing” will not predict shelf performance. That is why accelerated testing should include thermal cycling profiles that resemble real distribution rather than a single constant temperature.

| Channel point | Typical risk | Packaging lever | What to measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transport / last-mile | Heat spikes | Secondary packaging + handling rules | Bloom rate vs time |

| Retail shelf | Light + cycling | Light block + format choice | Whiteness/gloss + customer perception |

| Home use | Open-close exposure | Reseal system + instructions | Texture drift after opening |

Evidence (Source + Year): Sato et al. (2021) discuss mechanisms behind bloom formation and the role of storage conditions in accelerating visible defects.

Why do most shelf failures start at the seal, not the film?

Film specs can look perfect on paper, yet batches still fail on shelf. The reason is simple: seals carry the variance.

The seal system is the gatekeeper of barrier. If the seal becomes the leak path, the barrier layer does not matter, because oxygen and moisture will enter through the easiest route.

Seal geometry and contamination drive real-world variance

Flow wrap adds multiple seals, so the defect probability multiplies if process controls drift. Cold-seal systems also depend on coat consistency and clean sealing surfaces. Foil wraps depend on folds and overlap integrity, so small wrapping differences can cause large performance differences. Resealable pouches shift the dominant leak path after opening to the zipper interface, where consumer behavior and contamination variance are high. This is why “seal-variance failures” feel random in reviews. One customer stores a bag closed and clean. Another traps crumbs and leaves a micro-gap. Both believe they did the same thing. For buyers, the practical move is to validate seals as a system: seal strength, sealability window, and leak screening focused on the most likely paths for that format.

| Format | Most likely leak path | What buyers see | Fastest screening test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow wrap | Fin/back seal or end seals | Inconsistent aroma, early staling | Leak screening + seal strength |

| Foil wrap | Overlap/fold micro-gaps | Odor pickup, dryness/softness drift | Storage challenge + package checks |

| Resealable pouch | Zipper interface after opening | “Fine on day 1, stale later” | Open-close cycling + leak screen |

Evidence (Source + Year): ASTM F88/F88M (seal strength), ASTM F2029 (heat sealability mapping), and ASTM F2096 (bubble emission leak screening) are commonly used verification methods for flexible package seals and leak detection.

As a flexible packaging manufacturer, we focus on repeatability: the best spec is the one the line can seal consistently without creating the seal as the weakest link. See how we structure food packaging specs around seal window + leak-risk control.

How should buyers choose and validate for bars, truffles, and filled chocolates?

Chocolate “type” changes what drift dominates. Bars, truffles, and filled chocolates do not pay the same risk bill on shelf.

Bars often pay more for light/oxygen exposure, truffles pay more for moisture sensitivity and handling, and filled chocolates pay more for coupled internal migration plus external variability—so format choice should match the dominant risk on the real shelf timeline.

A simple decision matrix that prevents the wrong “upgrade”

Bars usually tolerate multi-serve handling better, but they can still suffer aroma loss and bloom if exposed to light and cycling. Flow wrap can work well for high-volume singles if seals are consistent. Foil wrap can work well when paired with a reliable secondary wrap or carton that reduces fold variance. Truffles and soft centers often demand tighter moisture control and gentler handling, so seal integrity and secondary protection matter more than “just thicker film.” Filled chocolates often have the highest risk of long-term drift, so buyers should prioritize consistent barrier plus consistent sealing, then validate with storage challenges that mimic distribution. Validation should not be academic. It should be tied to complaints: bloom visibility, texture drift, odor pickup, and “stale aroma.” The minimal proof pack should include seal robustness, leak screening, and an accelerated shelf challenge.

| Product type | Dominant drift risk | Format emphasis | Minimum validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bars | Light + oxygen + cycling | Light block + seal reliability | Thermal cycling + seal/leak checks |

| Truffles | Moisture sensitivity + handling | WVTR control + secondary protection | Humidity challenge + texture checks |

| Filled | Migration + external variability | Stable barrier + stable seals | Thermal cycling + bloom scoring + leak checks |

Evidence (Source + Year): Afoakwa (2009) summarizes how structure and storage conditions relate to bloom and quality defects. Svanberg (2012) discusses storage-driven changes in filled chocolate systems and how environmental exposure interacts with internal migration behavior.

What is the buyer-ready validation plan that matches real complaints?

Most teams test the film and forget the seal and the channel. Then complaints arrive from the weakest link.

A practical plan should prove three things: the package can seal consistently, the package does not leak at its most likely leak path, and the package controls drift under realistic shelf conditions.

The minimal proof pack is small, but it must be repeatable

The first step is seal robustness. Seal strength and sealability mapping show whether production is operating inside a safe window rather than relying on a single “good setting.” The second step is leak screening, focused on the most likely leak path for that format: flow-wrap seal lines, foil overlap zones, and zipper areas for resealable pouches. The third step is accelerated shelf challenge: a temperature cycling profile plus a humidity exposure profile that resembles the real market. Buyers should define pass/fail outcomes in plain language. No visible bloom at a defined week. Hardness stays within a defined range. No “stale odor” complaints in controlled sampling. Leak rate stays below a defined threshold. This approach turns format selection into a verifiable system decision instead of a material debate.

| Step | Purpose | Outcome | Common standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seal robustness | Process repeatability | Strength + window | ASTM F88/F88M, ASTM F2029 |

| Leak screening | Find weak path fast | Leak/no-leak + location | ASTM F2096 |

| Shelf challenge | Predict real drift | Bloom/texture/aroma trends | Buyer-defined protocol |

Evidence (Source + Year): ASTM F88/F88M (seal strength), ASTM F2029 (heat sealability), and ASTM F2096 (bubble emission) provide a standardized toolkit to verify seal and leak performance for flexible packages.

Conclusion

Foil, flow wrap, and resealable pouches can all win—if the seal system stays reliable and O₂/WVTR stay inside the shelf-life budget. Validate the leak path, not the marketing name.

Talk to JINYI about a barrier + seal system that matches your chocolate SKU

About Jinyi

Brand: Jinyi

Slogan: From Film to Finished—Done Right.

Website: https://jinyipackage.com/

Our mission: JINYI is a source manufacturer for flexible packaging. The goal is to deliver packaging that is reliable, practical, and ready to run—so brands spend less time clarifying details and get more stable quality, clearer lead times, and structures that match real shelf and transit conditions.

Who we are: JINYI is a source manufacturer specializing in custom flexible packaging solutions, with over 15 years of production experience serving food, snack, pet food, and daily consumer brands. We operate a standardized manufacturing facility equipped with multiple gravure printing lines as well as advanced HP digital printing systems, supporting both stable large-volume orders and flexible short runs with consistent quality. From material selection to finished pouches, we focus on process control, repeatability, and real-world performance.

FAQ

1) Is foil always the best choice for chocolate?

Foil can offer excellent light and aroma barrier, but the system can still fail if folds and overlaps create micro-gaps. Foil often performs best with a secondary overwrap or carton that reduces variance.

2) Why does flow wrap work for some brands but fail for others?

Flow wrap is highly sensitive to seal control. If seal surfaces are contaminated or seal pressure and dwell drift, leakage variance increases. The film can be “high barrier,” yet the seal becomes the leak path.

3) Are resealable pouches safe for chocolate shelf life?

Before opening, they can be excellent. After opening, zipper closure behavior becomes the dominant risk driver. Open-close cycling and contamination realism should be included in validation.

4) What causes “stale aroma” most often in retail chocolate?

It is commonly driven by oxygen exposure over time and by odor interactions in open retail environments. Strong barrier only helps when seal integrity is consistent.

5) What is the simplest validation set buyers should request?

Seal robustness (strength + window), leak screening focused on the most likely leak path, and an accelerated shelf challenge that includes temperature cycling and humidity exposure tied to the real channel.