Custom Pouches, Food & Snacks, Packaging Academy

Protein Snacks (Jerky, Bars, Bites): What Makes Buyers Trust “Freshness”—and What Triggers “Tastes Old” Reviews?

Buyers say “tastes old” fast, even when the product is safe. Brands often answer with bigger claims, and the backlash gets worse.

Freshness trust comes from measurable control: oxygen exposure, moisture drift, and clear “normal vs not normal” guidance. This article maps common reviews to real mechanisms and shows proof cues that reduce skepticism.

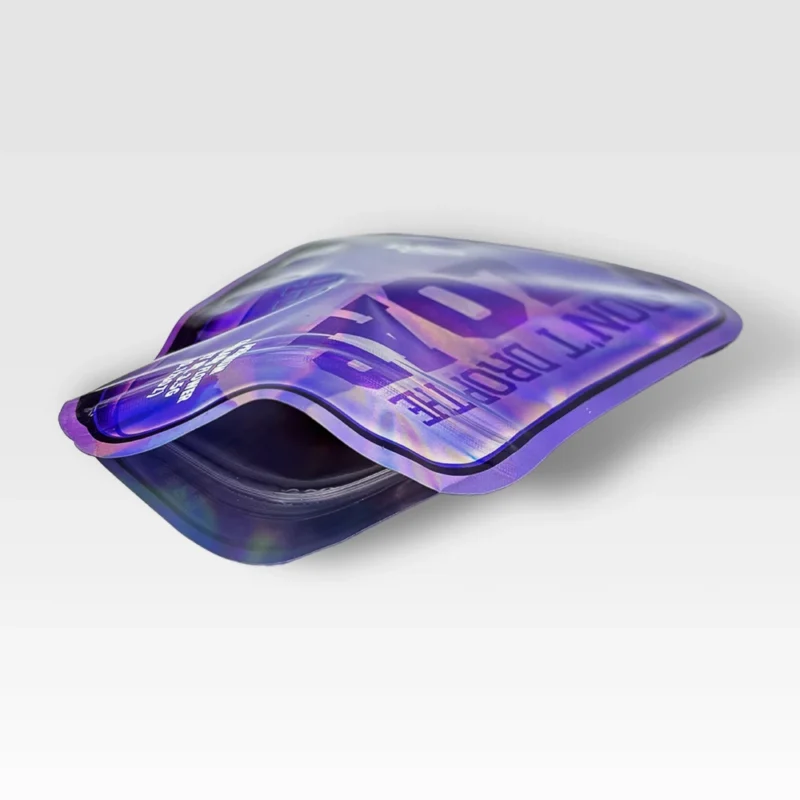

See food packaging formats that protect freshness signals without overclaiming

Protein snacks do not fail in one way. Jerky, bars, and bites have different “freshness engines.” Most negative reviews come from mismatched expectations, weak boundaries after opening, or packaging signals that do not match the product’s real risk.

What do buyers mean by “freshness,” and what do “tastes old” reviews actually measure?

Parents and athletes do not buy “freshness” as a word. They buy confidence that taste, smell, and texture will match the first bite.

This means “freshness” is a set of outcomes: no rancid notes, no off-odors, and a stable chew or bite within a realistic window.

As a flexible packaging manufacturer, we focus on packaging signals that buyers can verify: oxygen exposure control, moisture control, and reseal performance after opening.

Translate review phrases into mechanisms before changing packaging

Many teams treat “tastes old” as a branding problem. Buyers treat it as a risk signal. The fastest way to reduce repeat complaints is to translate emotional language into measurable pathways. “Tastes old / rancid” usually points to lipid oxidation, which accelerates with oxygen, heat exposure, and time. “Too hard / too dry” often points to moisture drift, which can happen even when flavor is fine. “Weird smell” can be oxidation, but it can also be odor absorption from storage or packaging materials. “Not fresh after opening” often indicates a missing post-open boundary: poor reseal, frequent opening, and humid kitchens change outcomes quickly. Once the team uses the same vocabulary for review phrases, quality checks, and on-pack guidance, the brand stops fighting customers and starts guiding them.

| Review phrase | Likely mechanism | What to check first | Buyer-facing proof cue |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Tastes old / rancid” | Lipid oxidation | Heat exposure + oxygen entry paths | Clear storage limits + “avoid heat” guidance |

| “Too hard / too dry” | Moisture drift | WVTR + reseal leakage + RH | “Best texture window after opening” |

| “Weird smell” | Oxidation or odor absorption | Neighbor odors + material odor + storage | “Store away from odors; reseal tight” |

Evidence (Source + Year): Frankel, Lipid Oxidation, 2nd ed. (2014); Rahman (ed.), FAO food stability / water activity framework (1999).

Jerky vs protein bars vs bites: which failure engines drive different complaints?

One “freshness” label does not fit all. Jerky, bars, and bites fail differently because their structures and fat/water systems differ.

Brands reduce returns when they set different proof cues for each format, instead of one generic “stays fresh” promise.

Match the proof cue to the product’s dominant risk

Jerky complaints often combine three drivers: oxidation notes, texture toughness, and occasional “off” odor after heat exposure. Bars often trigger “waxy,” “weird aftertaste,” or “hard as a rock,” which can be oxidation plus texture firming from moisture redistribution and cold storage. Bites often fail faster after opening because their surface area is high and packs are opened repeatedly, which increases oxygen and humidity exchange. The practical implication is simple: the best buyer-facing language changes by product type. Jerky needs heat and oxygen boundaries. Bars need “texture changes with temperature” expectations plus an opening window. Bites need reseal guidance and portion logic. If the brand uses one claim for all three, reviews become inconsistent, and buyers assume the brand is exaggerating.

| Category | Common complaint | Dominant risk | Most believable proof cue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jerky | “Rancid / old taste” | Oxidation + heat exposure | Heat-avoid guidance + realistic open-window |

| Protein bars | “Waxy / hard” | Oxidation + texture firming | “Texture varies with temperature” + open-window |

| Protein bites | “Stale quickly” | Post-open exchange | Reseal performance + portion packs guidance |

Evidence (Source + Year): Frankel, Lipid Oxidation, 2nd ed. (2014).

What triggers “tastes old” first: oxygen ingress, heat exposure, or formula sensitivity?

Most brands blame time. Buyers often experience “old taste” after a short period because oxygen and heat accelerate change.

“Tastes old” is often a system problem: oxygen entry paths plus heat exposure plus oil-sensitive ingredients.

Explain the three triggers as a chain, not three separate issues

Oxidation is strongly driven by oxygen availability and is accelerated by higher temperature. That is why “same batch, different reviews” is common. One buyer stores the product cool and sealed, and another leaves it in a warm car or near a stove. Formula sensitivity matters because oils, nuts, cocoa, and some coatings can show oxidation notes earlier than lean systems. The packaging side has to be described as “oxygen entry paths,” not only film OTR. Film transmission is one path, but micro-leaks, poor seals, and post-open reseal leakage can dominate the real oxygen exposure. The most trust-building approach is not to claim “always fresh.” It is to show buyers what conditions keep flavor stable and what conditions speed up staling.

| Trigger | What buyers notice | What brands should verify | Safer wording |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen ingress | Rancid / cardboard notes | OTR language + seal integrity thinking | “Designed to slow oxygen exposure” |

| Heat exposure | Old taste appears early | Route and storage temperature risk | “Store cool; avoid heat” |

| Formula sensitivity | Aftertaste, waxy notes | Oil source and oxidation sensitivity | “Best flavor within a realistic window” |

Evidence (Source + Year): ASTM D3985-24 (OTR test method language, 2024); Frankel, Lipid Oxidation, 2nd ed. (2014).

What triggers “too hard / too dry,” and why is it often mistaken as “stale”?

Buyers often call texture drift “stale.” That is why brands misdiagnose the problem and write the wrong claims.

Moisture drift happens when product water state shifts after opening, especially with weak reseal, high opening frequency, or extreme humidity.

Describe moisture as a system: product ↔ headspace ↔ film ↔ reseal ↔ room humidity

Texture stability depends on how fast moisture exchanges with the environment. Dry climates can pull moisture out of products over time. Humid kitchens can add moisture and create a softer or stickier bite, which some buyers interpret as “not fresh” or “not clean.” Bars can also firm up in colder conditions and feel “old” even when flavor is stable. The buyer needs boundary guidance that explains normal behavior. The brand also benefits from defining “best texture window after opening,” because that aligns with real household use. From a packaging perspective, WVTR language explains moisture barrier performance, but reseal performance often decides outcomes after opening. A strong “reseal tight” instruction without a time window is still vague. A credible message gives both: a reseal action and a realistic time horizon.

| Environment | Typical outcome | Buyer complaint | Expectation setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry / cold | Firmer texture | “Hard / stale” | “Texture firms in cold; allow to warm” |

| Humid / warm | Softer or tackier texture | “Weird / not fresh” | “Reseal tight; store cool and dry” |

| Frequent opening | Fast drift after opening | “Stale quickly” | “Best within X weeks after opening” |

Evidence (Source + Year): Rahman (ed.), FAO food stability / water activity framework (1999); ASTM F1249-13 (WVTR test method language, 2013).

Which proof cues build trust fast, and which claims backfire in protein snacks?

Buyers trust boundaries, not slogans. They reward brands that explain what to expect and how to store the product.

Claims backfire when they are absolute, untestable, or inconsistent with real home storage behavior.

Use “proof cue fields” that buyers can check in seconds

High-trust proof cues are specific and practical. Buyers accept that oxidation and moisture drift are real risks. They become skeptical when a brand implies perfection. The strongest pattern is a simple set of fields that match real buyer behavior: “store cool,” “avoid heat,” “reseal tight,” and “best within X weeks after opening.” A “normal vs not normal” block reduces arguments and support tickets because buyers can self-triage. The most common backfire phrases are “always fresh,” “never stale,” and “no odor guaranteed.” Those statements force buyers to hunt for exceptions, and one negative experience becomes a credibility collapse. A safer approach is to state what the packaging is designed to do and what conditions it assumes. That language is both buyer-friendly and risk-aware.

| Claim type | Buyer reaction | Backfire risk | Safer alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Always fresh” | Suspicion | High | “Designed to slow oxygen exposure” |

| “Never changes texture” | Easy to disprove | High | “Best texture within X weeks after opening” |

| Clear boundaries | Higher trust | Low | “Store cool, reseal tight, avoid odors” |

Evidence (Source + Year): Frankel, Lipid Oxidation, 2nd ed. (2014); ASTM D3985-24 (2024).

Want fewer “tastes old” reviews? Align packaging proof cues to your snack format

Conclusion

Buyers trust freshness when brands explain oxygen and moisture risks with clear limits. The fastest review wins come from proof cues, storage boundaries, and “normal vs not normal” rules.

Talk to JINYI about food packaging that protects freshness signals

FAQ

- Why do buyers say “tastes old” even before the best-by date? Buyers often experience heat exposure, oxygen ingress, or post-open drift that changes flavor earlier than they expect.

- Is “stale” always oxidation? No. Many “stale” reviews describe texture drift from moisture exchange, especially after opening.

- What is the fastest way to reduce “tastes old” reviews? Brands should publish clear storage boundaries, realistic post-open windows, and a “normal vs not normal” block.

- Which format is most sensitive after opening: jerky, bars, or bites? Bites often drift fastest because surface area and frequent opening increase oxygen and humidity exchange.

- Which claims should brands avoid? Brands should avoid absolutes like “always fresh,” “never stale,” or “no odor guaranteed,” because buyers can disprove them easily.

About Us

Brand: Jinyi

Slogan: From Film to Finished—Done Right.

Website: https://jinyipackage.com/

Our mission:

JINYI is a source manufacturer specializing in custom flexible packaging solutions. We want to deliver packaging that is reliable, usable, and easy to execute, so brands reduce communication costs and receive stable quality, clear lead times, and structure-matched printing results.

About us:

JINYI is a source manufacturer specializing in custom flexible packaging solutions, with over 15 years of production experience serving food, snack, pet food, and daily consumer brands.

We operate a standardized manufacturing facility equipped with multiple gravure printing lines as well as advanced HP digital printing systems, allowing us to support both stable large-volume orders and flexible short runs with consistent quality.

From material selection to finished pouches, we focus on process control, repeatability, and real-world performance. Our goal is to help brands reduce communication costs, achieve predictable quality, and ensure packaging performs reliably on shelf, in transit, and at end use.